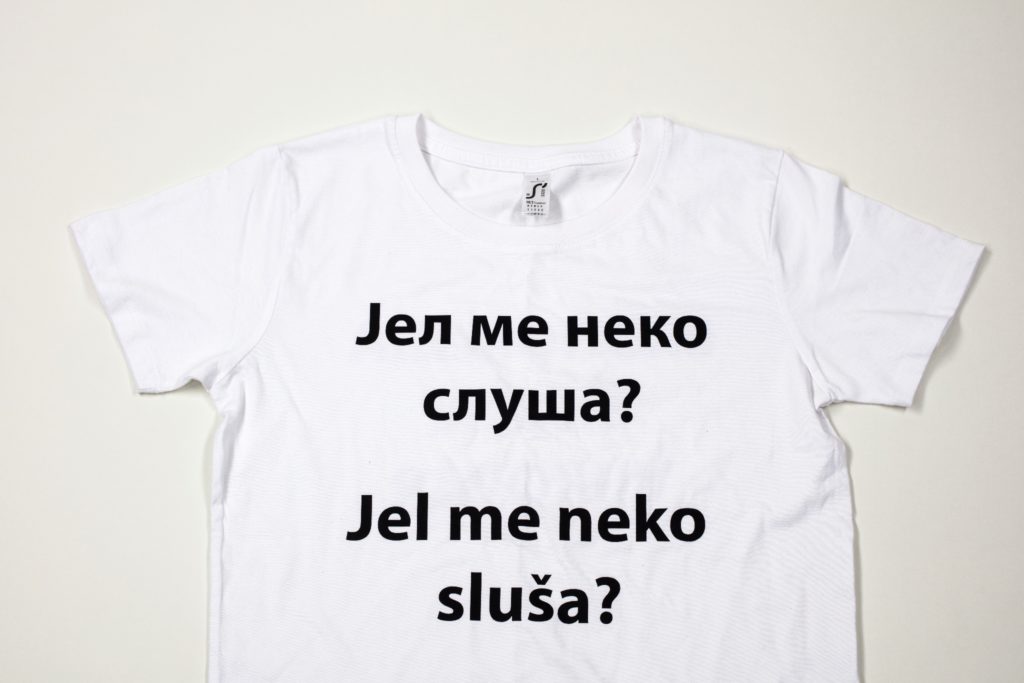

IS ANYONE PAYING ATTENTION?

On the last day of school, the graduates traditionally wear their graduation T-shirts. On mine, it reads “Is anyone paying attention?” because I tend to say it in class. They counted once, and I said it 30 times – but I think it was a double lesson. Or at least I hope it was! I’m saddened by the fact I had to take the T-shirt off when I arrived in Osijek. You must always bear in mind where you’re going and whether the environment accepts it. The Cyrillic script is still kind of exotic over here, it is as if all of us never learned it.

Marijana Radmilović, teacher of Croatian language and literature

Is anyone paying attention? has a double meaning: on the one hand, the storyteller’s need to be heard and understood, and on the other hand, the moment at which we start paying attention to the storyteller. This is the moment in which the storyteller addresses us in a language that is contextually and formally calibrated for us, the audience, in an acceptable manner. Otherwise, we often stop paying attention. And we often do not wonder as to what we have failed to hear by deciding this.

In the last thirty years or so, there have been few opportunities to listen to the stories of Osijek’s Serbs in one place. The collaboration with individuals who feel their Serbian identity more strongly and those who do not see themselves as part of the minority community yielded this selection of narrators and their stories. The narrators’ topics and preoccupations depended on their age, interests, experience. That which strongly marked all of them is the life in Osijek and connectedness with the city on the Drava river.

The year 1991 was crucial for all citizens of Croatia: the war began with which Serbia and Montenegro sought to prevent independence of Croatia and the creation of a sovereign state. Many social relationships dissolved, and the cards between the political and social elites were reshuffled. The dissolution of socialist Yugoslavia led to the revival and questioning of national identities and to conflicts therefor.

According to the 1991 Census, the city of Osijek had a total of 104,761 residents. Just before the war, in the city lived 70.9% of Croats (74,254), 15.2% of Serbs (15,985), and 5.7% (6015) of Yugoslavs. Thirty years later, according to the 2021 Census, there are 96,313 residents in Osijek, of which only 4,188 are Serbian (4.35%). The number of Serbs in the city’s population structure has been in continual decline over the last thirty years or so. Ten years earlier, according to the 2011 Census, there were 6,751 or 6.25% of Serbs in Osijek. One of the reasons for this constant decline in the number of Serbs in Osijek’s population structure is, according to Škiljan (Dragutin Babić, Filip Škiljan and Drago Župarić-Iljić, “Identitet Srba u Hrvatskoj,” Politička misao, year 51, no. 2, 2014), ethnomimicry, assimilation as a form of abandoning the cultural attributes of Serbian identity, which grew stronger during and immediately after the war, as well as the avoidance of status anxiety (qtd. in: Jelena Marković, “Šutnje straha,” 2024), i.e., withholding (part of) own identity, which is perceived among members of the majority population as undesirable or negative. Furthermore, a portion of members of the Serbian national minority, especially urban and young people, prefer the supranational identity, while the persons with mixed origin prefer the multiethnic identity (“Identitet Srba u Hrvatskoj,” Politička misao, year 51, no. 2, 2014).

On the other hand, meritorious for preserving the language, religion and culture as attributes of the identity of Serbs in Osijek are the cultural associations and the denomination (e.g., the Osijek sub-committee of the Serbian Cultural Society “Prosvjeta,” which dates back to 1945, and the Serbian Orthodox Church).

Most of the middle-and-older-generation residents of Osijek have been marked by the war. On 27 June 1991, a tank of the hitherto joint Yugoslav People’s Army ran over a small red Fiat 600. This act paved the way to the destruction of hitherto social relationships at the symbolic and actual levels. Many residents of Osijek were killed under the “caterpillar tracks of the war,” including numerous civilians of Serbian nationality. During the war, they were the ones who, as collectively labelled enemies, shouldered the weight of their compatriots who proclaimed their territory (the so-called Serbian autonomous regions) in part of the territory of Croatia, and systematically bombarded the city from the vicinity of Osijek between September of 1991 and the signing of the Sarajevo Truce in January of 1992. In the wartime years, many residents of Osijek of Serbian nationality were banished from their homes, many of them lost their jobs, and some of them were tortured and executed for suspicion or false accusation of terrorism.

And while the traumas of the majority population have been recognised and communicated in public, interest or understanding is seldom shown towards the traumas and experiences of members of Osijek’s Serbian community. Despite this, the storytelling of minority members in public space is of immense importance. It acknowledges the storytellers, gives them a voice, and brings new value into the lives of those who want to hear their stories. When deliberating on the importance of the opportunity for dialogue that heals the entire community, German philosopher and psychiatrist Karl Jaspers writes as follows: “It is so easy to stand with emotional emphasis on decisive judgments; it is difficult calmly to visualise and to see truth in full knowledge of all objects. It is easy to break off communication with defiant assertions; it is difficult ceaselessly, beyond assertions, to enter on the ground of truth. It is easy to seize an opinion and hold onto it, dispensing with further cogitation; it is difficult to advance step by step and never to bar further questioning. We must restore the readiness to think […] One requirement is that we do not intoxicate ourselves with feelings of pride, of despair, of indignation, of defiance, of revenge, of scorn, but that we put these feelings on ice and perceive reality.” (Karl Jaspers: “Pitanje krivnje,” 2006).

The mentally unprocessed interethnic relationships trapped in the narratives of the war and postwar period constitute an obstacle in the process of building contemporary identities of civilians of Serbian nationality, and on the other hand, they constitute an obstacle to the generally accepted narratives of the majority population in relation to the Serbian minority: Who are the Serbs? How do we feel about them? What could change in this case, and in which manner do they participate in the Croatian society?

The personal narratives of Osijek’s residents of Serbian nationality, regardless of their severity, specificity or universality, are one of the opportunities to establish relationships where they are not yet present, but may come to life. In this setup, we present 18 personal stories of Osijek’s Serbs of different generations and with different attitudes towards Osijek. Some of the storytellers even lived through the Second World War, many of them grew up and lived in Yugoslavia, a portion of them come from mixed marriages, part of them were born during the dissolution of Yugoslavia and afterwards, in independent Croatia, some of them moved out of Osijek, while some chose Osijek as the city in which they sought to build life or raise their children. The storytellers have different occupations, experiences, perceptions of themselves and their role in the society in which they live. They present themselves to the audience with a photo portrait, a sketch from their personal narrative, a video interview, and a personal item that is symbolically connected to their personal story. In this setup, they describe significant moments in their lives which have marked them, they speak of the difficult and nice things for which they fought and which changed them. By communicating themselves, the storytellers reflect the wider social community and reexamine the universal topics which make us human.

Martina Globočnik