1. WHERE THE FACTORY LIVES, THE CITY LIVES

Ethnography of social and economic disaster is a term coined by Michael Burawoy after 40 years of studying the ethnography of workplaces (from Potkonjak and Škokić: Where does the factory live? Ethnography of the post-industrial city). Burawoy talks about the fact that, since the beginning of 1990, the collapse of the economy has been closely linked to the collapse of urban centers around the world. The de-industrialization of Osijek, which has been going on since the early 1990s until today, is visible through the process of physical transformation on city maps, but also in the narratives of the citizens of Osijek who participated in this process. On the example of the fate of Osijek’s textile industry, whose flywheel was felt in socialism, and collapse and devastation during and after the Balkan Wars, through the process of conversion and privatization, we can observe Osijek as a city that has been undergoing a complex social and economic transformation in the last three decades. Moreover, the still present scars of the war, the drop in production, the impoverishment of citizens and the noticeable drop in the number of inhabitants can be seen through the stories of the protagonists, but also through photographs, showing the changes in the city’s urbanism.

According to the 2021 population census, 75,916 people live in the city of Osijek. The decline in numbers has been noticeable over the decades: in 1991, there were 104,761 inhabitants, in 2001 there were 90,411, and in 2011 there were 84,104 inhabitants. At the locations of Slavonija Fashion Confectionery Industry (IMKS), Osijek Linen Industry (LIO), Osijek Textile Industry (TEKOS), Mara – Knitwear Factory, and the Osijek Silk Weaving (Svilana Osijek), an intention is clearly visible – the start of designing non-industrial content, while valorization of the social value of these factories (as examples of industrial heritage) is missing. Traces of the reinterpretation of space are visible in the repurposing of space into, for example, warehouses, and a pet store at the LIO location, in the ruining of former industrial complexes (Leather Factory), evident in the example of Orthopedic Technique Osijek (OTOS).

Guided by the idea that where the factory lives, the city lives, the former largest textile factories and existing business initiatives in Osijek were drawn on the map of Osijek. Treated in this way, they are not experienced as relics of the past, whose place and role have been taken over by the IT sector and catering, but as meeting places of the city and its inhabitants.

2. STORIES OF TEXTILE WORKERS IN THE TOWN OF OSIJEK

“I wouldn’t let my dog be a textile worker. No. Never. Because a person working in textiles can only earn a hump on their back. An old saying goes: You can be as rich from textiles, only as the shade your needle makes. That’s exactly how it is. It used to be funny to me. In the end, I realized that it was true.”

Draginja Jakobfi, Slavonija fashion clothing industry

As stories about the loss of jobs of female textile workers, due to their hopeless fate, entered the mainstream media, and became part of the general narrative, the question arose to whether we as an audience (and citizens) had become insensitive to other people’s suffering and incapable of compassion? Insensitive to what is always fresh, engaging, human, to what can cause an emotional reaction from us, as observers? What actually, while observing and listening to others, makes us find a spot that is vulnerable and/or moral within ourselves?

The presented personal narratives simultaneously represent testimonies of the erased history of Osijek as an industrial center and personally intoned records of one’s own challenges, successes, and overcoming life’s dramatic moments. In the subtext of the narrative of former workers lies the fact that this predominantly female and socially sensitive work environment, that in the past had meant educational and social emancipation of workers, became their fatal trap in the era of privatization. Many workers who worked according to the norm failed to adapt to the market. Their professional focus on a single operation made them less competitive in the search for a job in the profession. Many female workers end their working life by retiring or re-training. Many of them, unfortunately, become nameless participants in the impoverished Croatian reality, while only a small part of female workers is employed in the production facilities of a small number of domestic entrepreneurs or foreign corporations. Only the rare, brave and persistent ones open their trades: tailor shops.

The space of personal stories, as a microcosm of the narrators, is the stage of their experiences where they bear witness to what was hushed up or ignored because they did not have the opportunity to talk. Giving our narrators a voice is a process of recognizing the value and restoring the dignity of women who carried what economists call the transition on their shoulders: the transition from a centrally planned socialist economy to a market economy through the process of privatization. However, it is also about opening up space for individual reflections on victories and defeats, sketches from work, anecdotes and turning points, when personal experience and memory help the observer to understand what is hidden behind the concept of a “textile factory” and what it intimately meant to the narrators.

Although modest pay and unenviable working conditions have always prevailed in the experiences of workers in textile factories, many narrators of this set symbolically weigh and compare then and now: the romantic period of socialism and the harsh time of capitalism.

Observing the set of personal stories of textile workers in the city of Osijek, this can be taken with a reservation, but also with understanding. Chiara Bonfiglioli, based on research on the collapse of the textile industry in Yugoslavia, concludes that “despite the loss of hundreds of thousands of jobs in the textile industry since 1989, the socialist industrial structure of feeling continues to inhabit workers’ stories and imaginations, providing a generational, gendered, and class-based framework through which to interpret economic, political and social transformations of the 1990s and 2000s.” (from Potkonjak and Škokić: Where does the factory live? Ethnography of the post-industrial city).

The bearers of personal stories are introduced to the lineup with a photographic portrait, a summary (part of the personal narrative) and a video interview. Their testimonies are an attempt to speak out loud about the perseverance of the personal struggle for their own existence and the prosperity of their

3. A DIFFERENT FUTURE OF TEXTILES IS POSSIBLE!

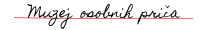

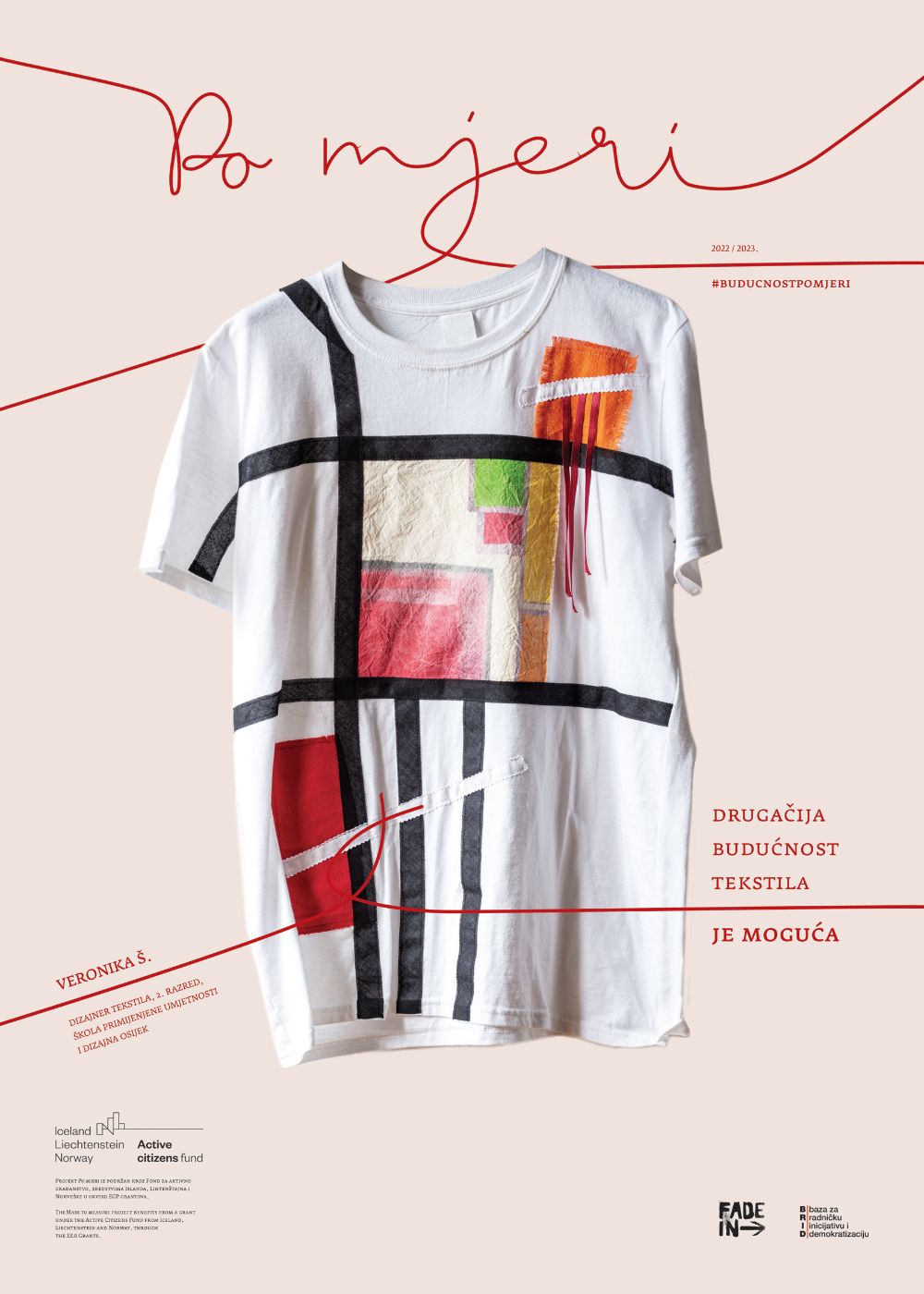

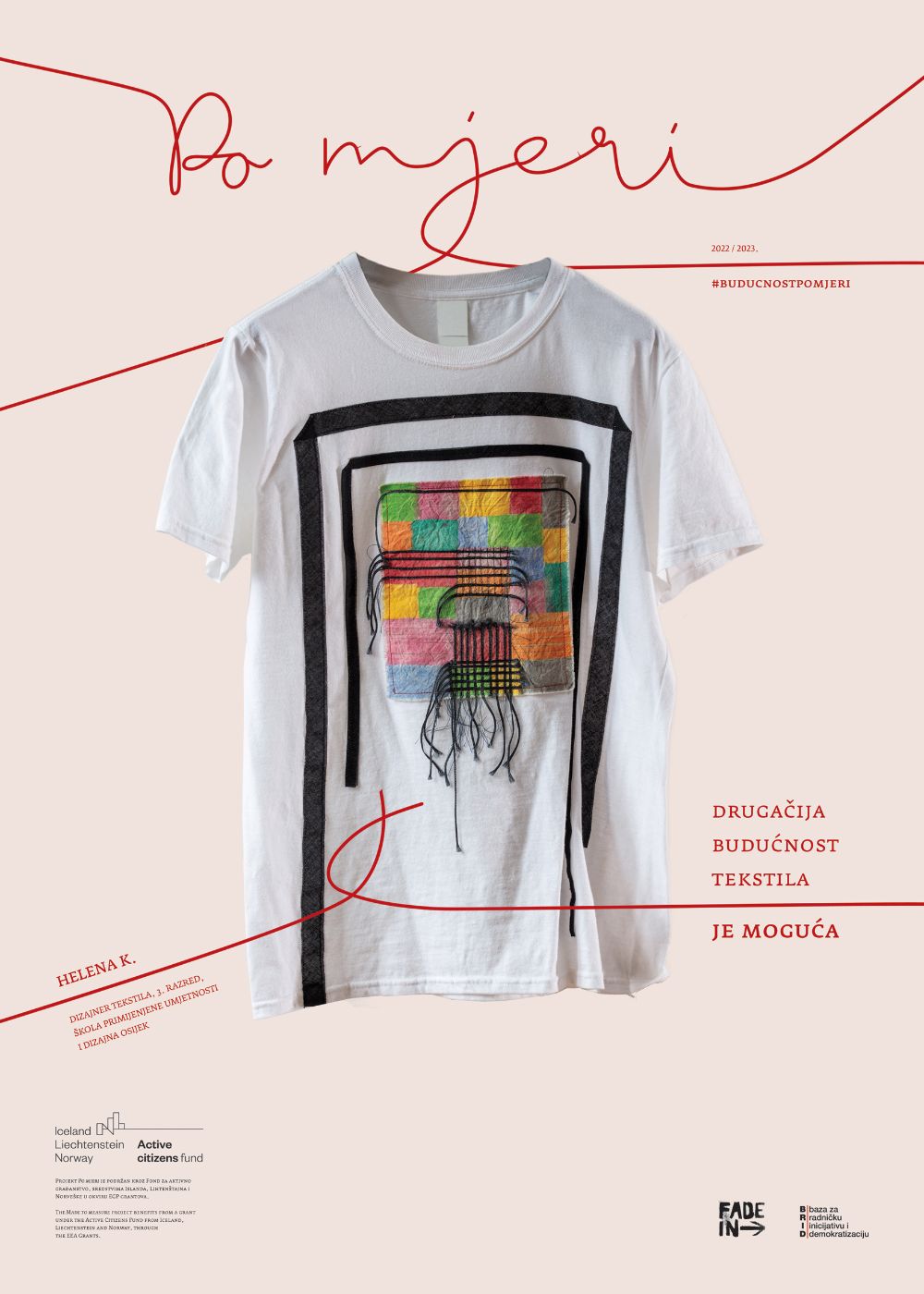

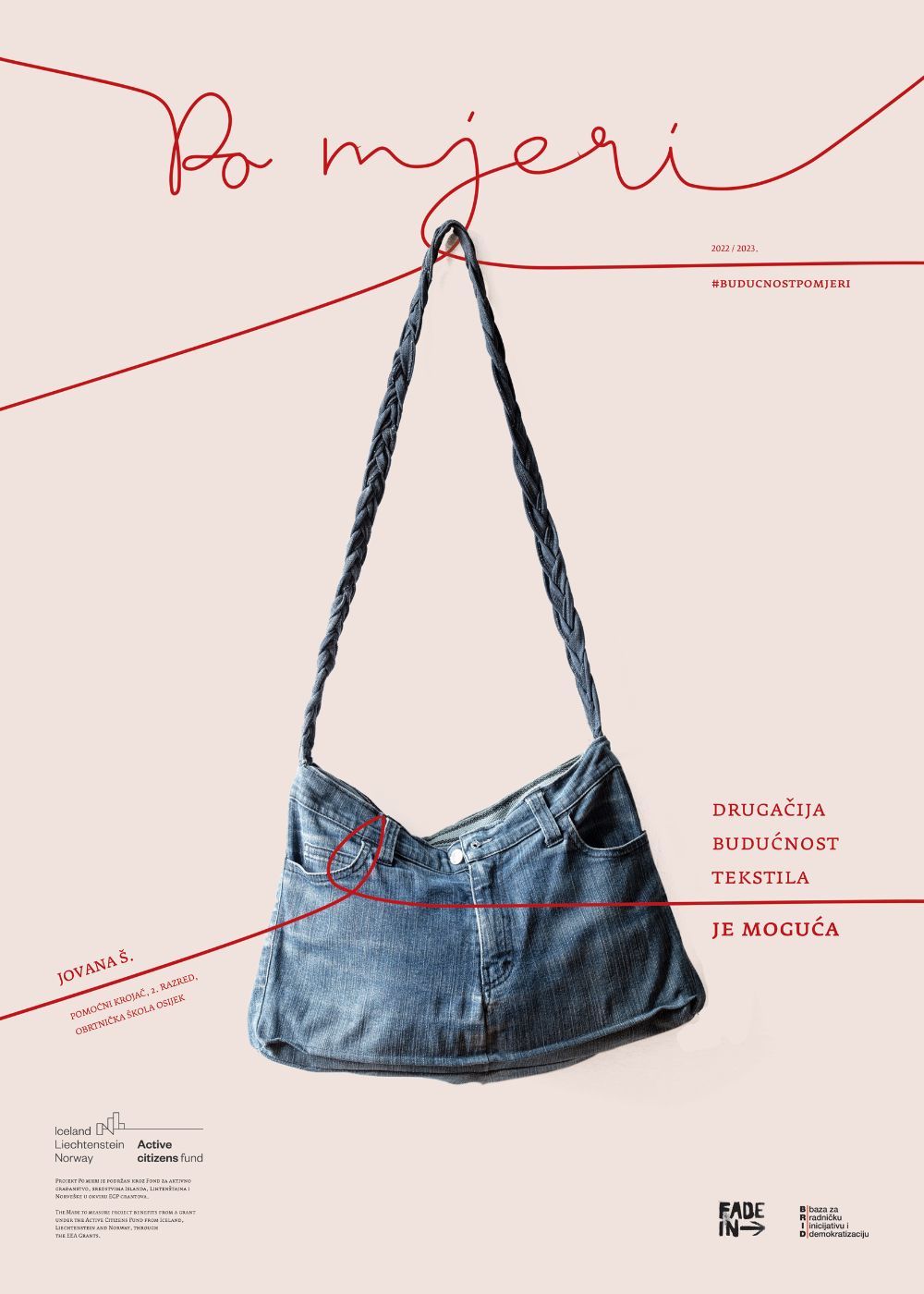

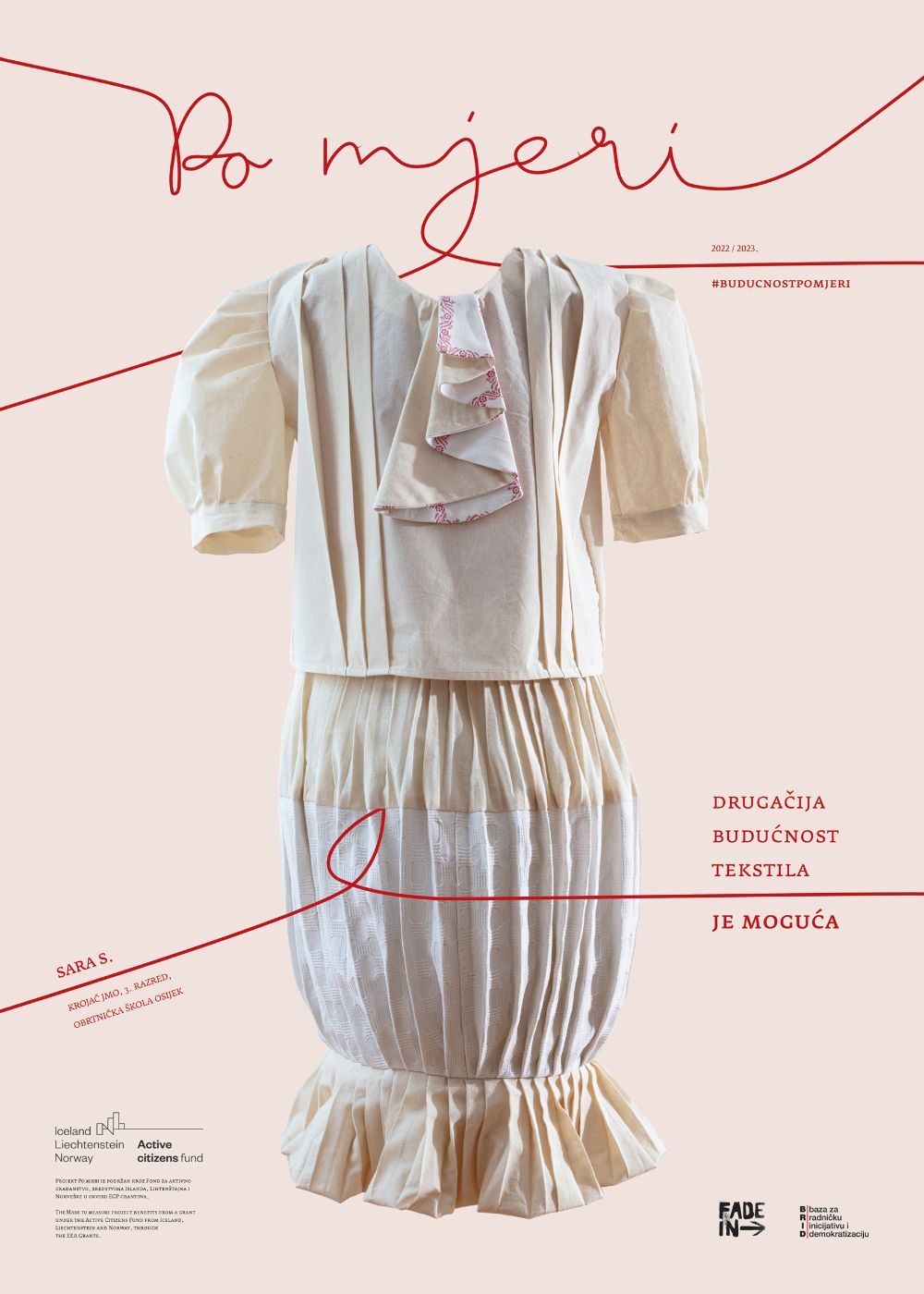

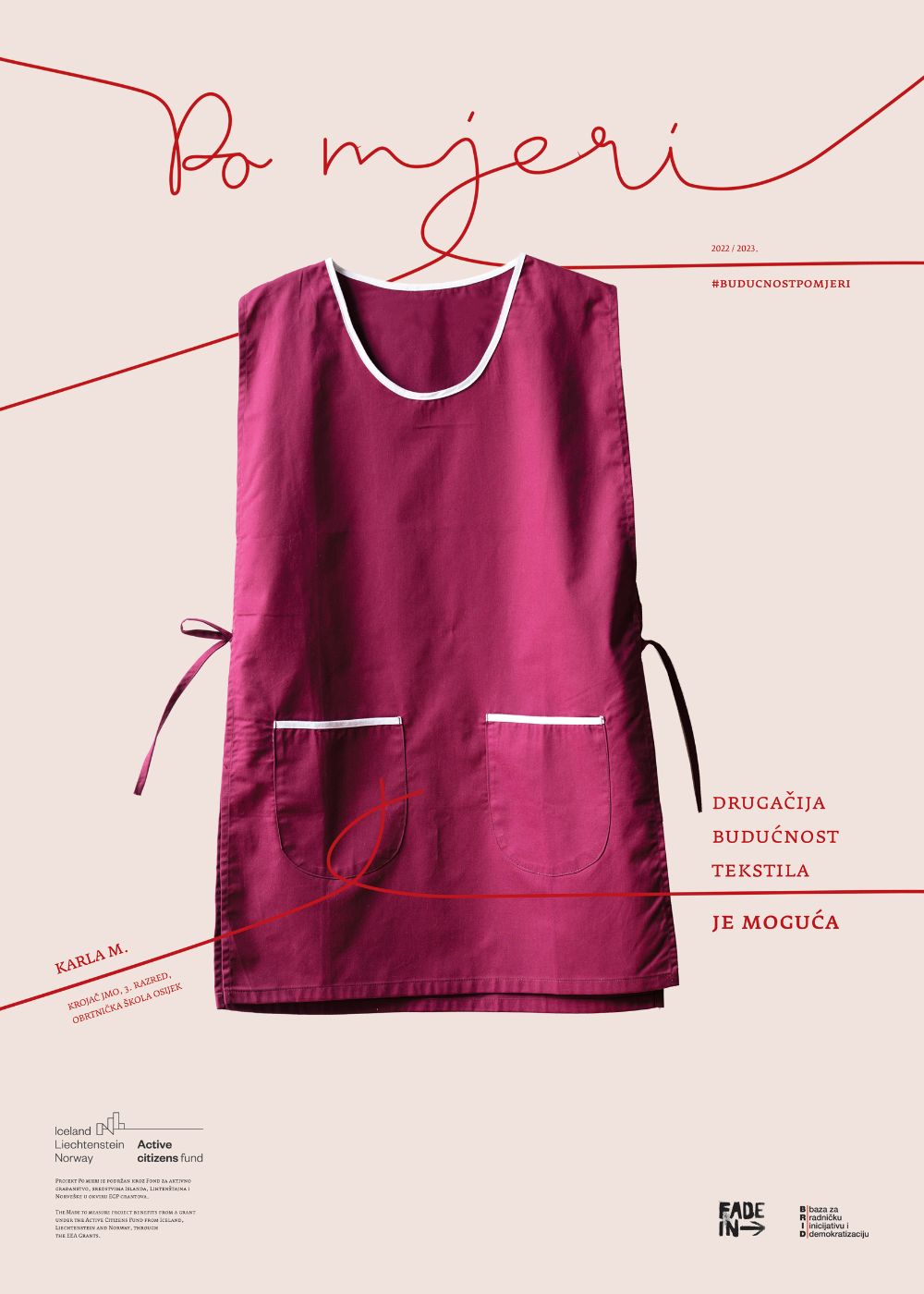

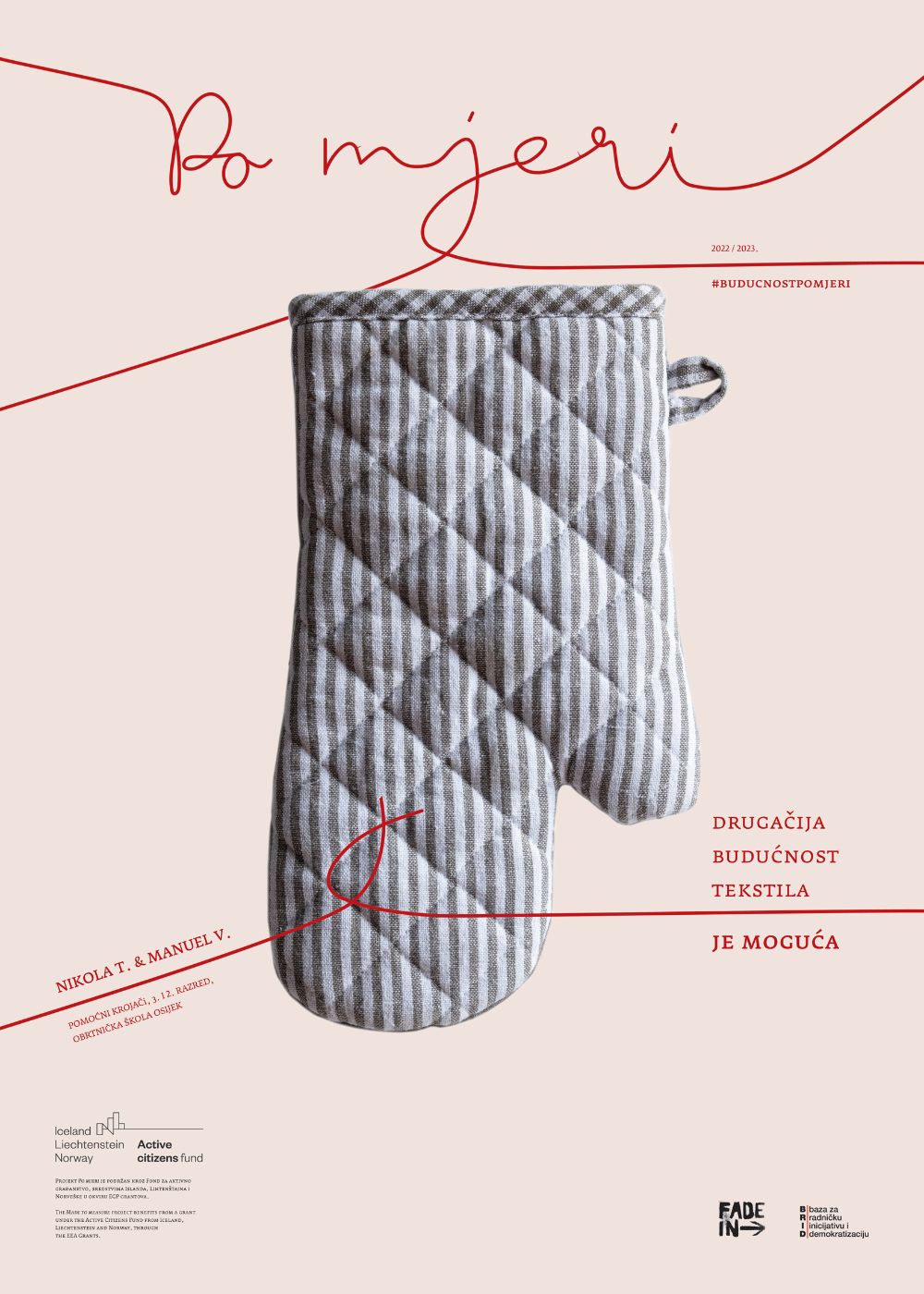

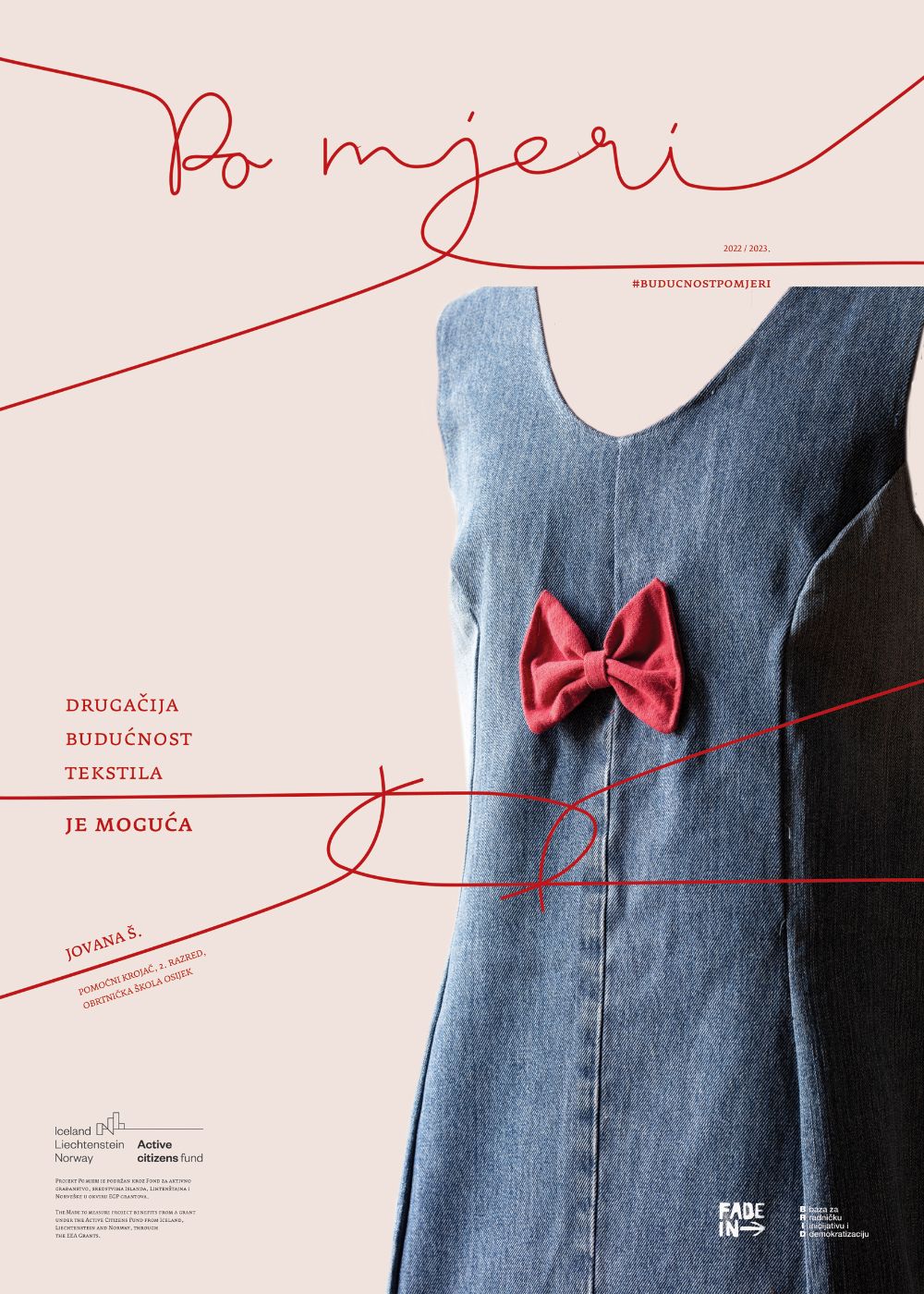

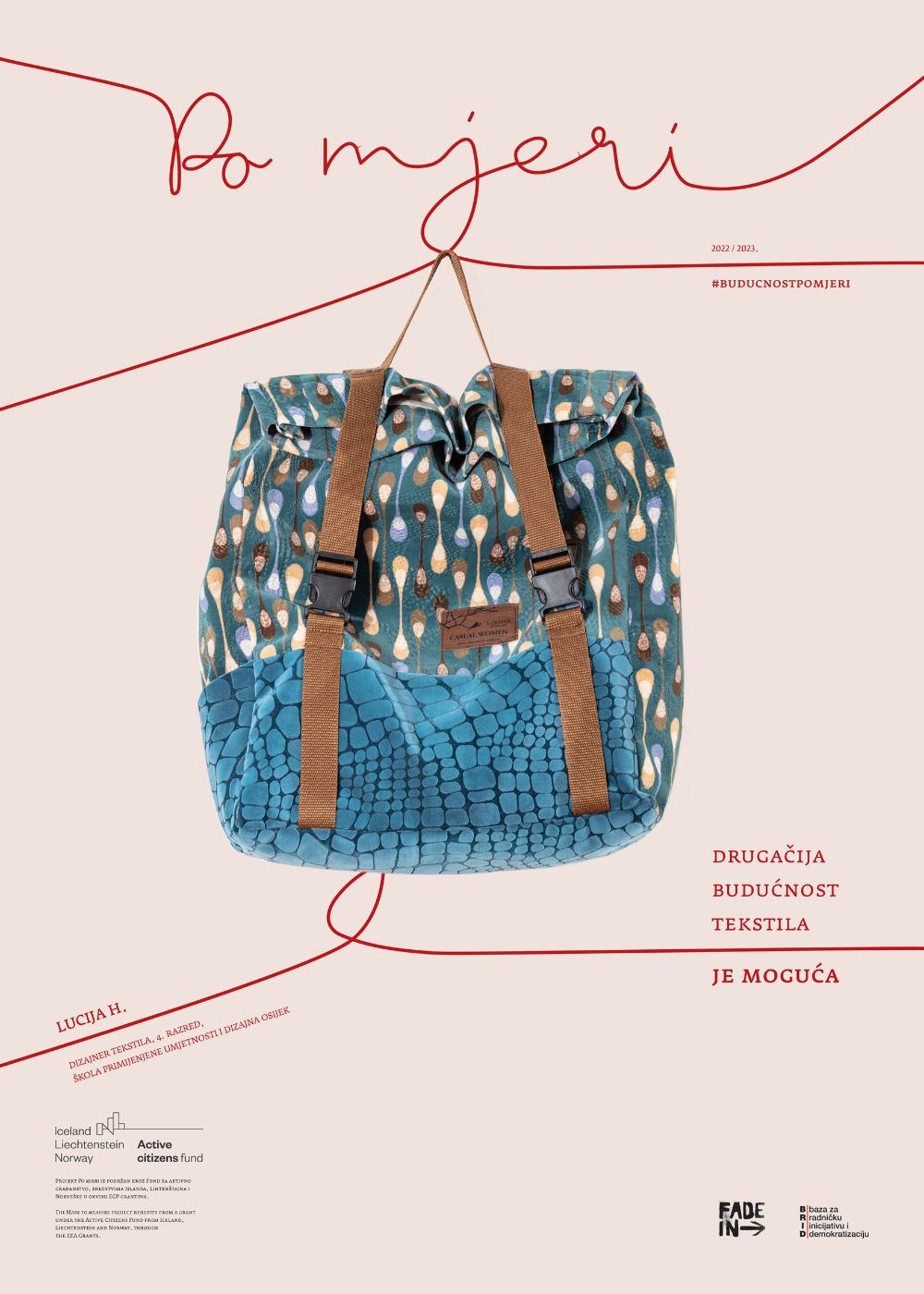

In the circumstances of the decrease in the production of clothing and textiles in Croatia, the position of the students of the Trade School Osijek (occupations “tailor” and “assistant tailor”) and the School of Applied Art and Design Osijek (occupation “textile designer”) was advocated through the mobile exhibition as a vital part of our project.

As future workers, students are presented through photographs of their school work in the form of posters. On the posters, along with the works of high school students, there is an inclusive message: A different future of textiles is possible! The mobile exhibition encourages questioning and imagining the future of textile production and is set up as a moving exhibition in cities where the textile industry exists, or where it is part of the heritage. The exhibition is simultaneously organized in Zagreb, Osijek, Požega and Čakovec, in agreement and with the support of local tailor salon owners. The process of moving students’ works from the gallery to the public or business space communicates the challenges of the professions themselves.

The narrowness of the windows of tailoring shops, where posters with photos of students’ works are displayed, is very different from the spatial voluminosity of the former factory complexes. This modesty speaks of the inferior, marginalized position of the future textile worker, and on the other hand, the presentation of their idea, their work, themselves.

The setting is about the symbolic confrontation of passers-by, us from the outside, with people who observe us from the inside, from the point of view of tailors and textile designers. The message that stands next to the students’ works, that a different future of textiles is possible, calls for synergy, reflection and social responsibility. Averting our eyes and the lack of vision has ruined the future of many previous communities, and is on a determined path to ruining the future of this generation as well.

A long-time teacher of practical classes for assistant tailors from the Osijek Trade School states: “The profession of tailoring has a future. Society’s perception is wrong as far as craft occupations are concerned. You can make a good living from it. There will be a shortage of tailors and the job will be better paid.”

And while the socialist concept of clothing and textile industry implied a large number of workers, and employed various profiles of experts and craftsmen (designers, constructors, seamstresses), today’s industrial model exists in a vacuum driven by fast profits from foreign companies and efforts from small and medium-sized entrepreneurs. Although the prevailing anachronistic clothing and textile industry does not actually need workers, but alienated subsidized seamstresses and machine operators instead, the modern era textile industry is rapidly approaching. It is certain that, after the adaptation of textile and clothing manufacturers to contemporary trends that focus on the circular economy, original domestic design, processing of recycled clothing and sustainable fashion, it will be possible and also necessary to design an appropriate educational framework that will train promising future workers.

Martina Globočnik

GALLERY

English title of the project: Made to Measure

Project coordinator: Incredibly good institution – FADE IN

Partners: Organization for Workers’ Initiative and Democratization

Duration of the project: 1. 10. 2022. to 30. 9. 2023.

Total value of the project: 88.980,49 € of which €88,980.49 is secured through financial support from Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway within the framework of the European Economic Area and Norwegian grants

Contact for more information: Morana Ikić Komljenović e-mail morana.komljenovic@gmail.com

Links to relevant websites: www.fadein.hr (website of the project coordinator), https://muzejosobnihprica.com/ (Museum of personal stories), Facebook: @fadeinhr @muzejosobnihprica Instagram: @muzej_osobnih_prica

Objavljeni sadržaj se temelji na osobnim iskazima i subjektivnom doživljaju bivših i sadašnjih radnica i ostalih sudionika aktivnosti projekta PO MJERI i ne predstavlja nužno stavove i iskustvo organizacija Fade In i BRID.